Director Shogoro Nishimura was best known for his Roman Porno films, which have always enjoyed immense commercial popularity despite their modest cinematic merits. However, before Nishimura became a Roman Porno vending machine, he was a yakuza and youth film director at Nikkatsu. Those early films, which account to 14 in total, made between 1963 and 1970, reveal a far more interesting filmmaker than the gun-for-hire that most people know him as.

Director Shogoro Nishimura was best known for his Roman Porno films, which have always enjoyed immense commercial popularity despite their modest cinematic merits. However, before Nishimura became a Roman Porno vending machine, he was a yakuza and youth film director at Nikkatsu. Those early films, which account to 14 in total, made between 1963 and 1970, reveal a far more interesting filmmaker than the gun-for-hire that most people know him as.

Nishimura passed away in August 2017. In January 2018 Cinema Vera in Tokyo held a commemorative 14 film Nishimura retrospective, titled “Re-Evaluating Shogoro Nishimura”, which included eight of his Roman Porno films as well as six early features from his mainstream years. The latter remain difficult to see as hardly any of them have been released on DVD. Let’s take a closer look at the films screened in the retrospective.

Nishimura’s directorial debut was the 1963 film The Gambling Monk (Keirin shônin gyôjyôki / 競輪上人行状記), based on a screenplay by Shohei Imamura and Nobuyuki Onishi. The film is a biting black comedy/drama about a mischievous middle school teacher (Shoichi Ozawa) who becomes a gambling addicted monk following his brother’s death. He tries to take care of his family temple business, but gets mixed up in bicycle betting, alcohol and desperate women.

Nishimura’s directorial debut was the 1963 film The Gambling Monk (Keirin shônin gyôjyôki / 競輪上人行状記), based on a screenplay by Shohei Imamura and Nobuyuki Onishi. The film is a biting black comedy/drama about a mischievous middle school teacher (Shoichi Ozawa) who becomes a gambling addicted monk following his brother’s death. He tries to take care of his family temple business, but gets mixed up in bicycle betting, alcohol and desperate women.

Although not a film tailored for my personal tastes, fans of Imamura and Japanese 60s new wave ought to be in for a threat. The mix of dark drama, comedy and social satire aiming to spark some controversy is especially reminiscent of Imamura’s films. It is then perhaps not surprising that, despite being adored by critics, the film bombed in theatres upon its release and brought Nishimura’s career to an instant end for three years. It remains a forgotten film waiting to be discovered.

Nishimura got his second chance at directing in 1966 with the excellent Sun Tribe film Kaettekita ookami (帰ってきた狼). The story kicks off when a mixed blood, misunderstood loner (Ken Yamauchi) drifts back into a small seaside town where he slew a man years ago. Around the same time a super hot yacht girl Rika, who is a bit of a spoiled brat, sails to the shores. She has instant hot for him, and her bloated self ego takes a hit when he says he just digs her yacht. Then there is the film’s actual protagonist (Junichi Kagiyama), a cowardish but decent guy and the only rational one of the bunch, as well as some local teen hoods giving everyone trouble.

Nishimura got his second chance at directing in 1966 with the excellent Sun Tribe film Kaettekita ookami (帰ってきた狼). The story kicks off when a mixed blood, misunderstood loner (Ken Yamauchi) drifts back into a small seaside town where he slew a man years ago. Around the same time a super hot yacht girl Rika, who is a bit of a spoiled brat, sails to the shores. She has instant hot for him, and her bloated self ego takes a hit when he says he just digs her yacht. Then there is the film’s actual protagonist (Junichi Kagiyama), a cowardish but decent guy and the only rational one of the bunch, as well as some local teen hoods giving everyone trouble.

Kaettekita ookami is almost everything a good Sun Tribe film should be: yachts, motor boats, guitars, fights and burning teen passion, all packed into 78 minutes. The characters are excellent, there’s a constant aura of energy to Nishimura’s direction, and most importantly the Taiwanese-Japanese actress Judy Ongg is just amazingly hot and badass as Rika. When director Nishimura, in an unrelated interview, expressed his regret that much of the Roman Porno genre that later employed him may be problematic from a female perspective, I wondered if he truly cared. But seeing movies like this, with show stealing female characters, I can believe he really meant what he said. Fantastic film!

Note: I cannot find an English title for Kaettekita ookami anywhere. The Japanese title translates as “Return of the Wolf”, referring to the character played by Ken Yamauchi.

Following Kaettekita ookami, Nishimura helmed a number of other films I have not had the pleasure of seeing. However, his 1967 effort Burning Nature (Hana wo kuu mushi / 花を喰う蟲) offers further evidence that Nishimura is indeed remembered for the wrong films. This one starts out as a breezy youth film but soon morphs into a study of greed and moral corruption as a wildcat girl (Taichi Kiwako) runs into a manipulative “businessman” (Hideaki Nitani) who promises her a career as a model. She finds success due to her good looks, but also learns that that is exactly her worth the in the modern world.

Following Kaettekita ookami, Nishimura helmed a number of other films I have not had the pleasure of seeing. However, his 1967 effort Burning Nature (Hana wo kuu mushi / 花を喰う蟲) offers further evidence that Nishimura is indeed remembered for the wrong films. This one starts out as a breezy youth film but soon morphs into a study of greed and moral corruption as a wildcat girl (Taichi Kiwako) runs into a manipulative “businessman” (Hideaki Nitani) who promises her a career as a model. She finds success due to her good looks, but also learns that that is exactly her worth the in the modern world.

It’s a stylish film and features a terrific leading performance by Taichi Kiwako. Eiji Go, an actor best known for portraying crazed yakuza, is also very good as a young man in love with the protagonist. Meiko Kaji has a small supporting role. The film’s only problem is that it can’t quite keep the wonderful momentum it establishes during the superb first half till the very end.

It’s also worth mentioning as a piece of trivia that Burning Nature opened as a double feature with Seijun Suzuki’s Branded to Kill (1967), a film that ended Suzuki’s career at Nikkatsu.

Not all early Nishimura films were great, though. Tokyo Streetfighting (Tokyo Shigai sen / 東京市街戦) (1967) is a case in point. Tetsuya Watari’s theme song is the only good thing about this half-arsed Nikkatsu yakuza action film. It’s yet another tale of people coping in the ruins of Tokyo in the post WW2 Japan, with a couple of good men (Watari, Joe Shishido) standing against the exploitative Korean gangsters. Toei also made several films like this, some of them good (True Account of Ginza Tortures, 1973), some as bad as this (Third Generation Boss, 1974; Kobe International Gang, 1975).

Not all early Nishimura films were great, though. Tokyo Streetfighting (Tokyo Shigai sen / 東京市街戦) (1967) is a case in point. Tetsuya Watari’s theme song is the only good thing about this half-arsed Nikkatsu yakuza action film. It’s yet another tale of people coping in the ruins of Tokyo in the post WW2 Japan, with a couple of good men (Watari, Joe Shishido) standing against the exploitative Korean gangsters. Toei also made several films like this, some of them good (True Account of Ginza Tortures, 1973), some as bad as this (Third Generation Boss, 1974; Kobe International Gang, 1975).

With its uninspired performances, routine execution and a programmer storyline aiming to connect with the more sentimental and nationalistically minded viewers (there even an orphan boy and his blind sister suffering in the slums!), Tokyo Streetfighting offers little to be impressed about. Even the final street war / machinegun massacre fails to thrill, despite its unbelievable body count. A thoroughly underwhelming effort by Nishimura.

Another example of lesser efforts in Nishimura’s filmography is Biographies of Killers (Shikakû rêtsuden / 刺客列伝) (1967). Nikkatsu was in general best known for their contemporary films, however, they also produced scores of period yakuza films. I am far from well educated in Nikkatsu’s yakuza output, but compared to Toei’s ninkyo films, this movie at least is somewhat grittier in philosophy (as suggested by the title), leaving less room for chivalry, stoic pathos and manly bonding than you’d find in your average Ken Takakura or Koji Tsuruta film.

Another example of lesser efforts in Nishimura’s filmography is Biographies of Killers (Shikakû rêtsuden / 刺客列伝) (1967). Nikkatsu was in general best known for their contemporary films, however, they also produced scores of period yakuza films. I am far from well educated in Nikkatsu’s yakuza output, but compared to Toei’s ninkyo films, this movie at least is somewhat grittier in philosophy (as suggested by the title), leaving less room for chivalry, stoic pathos and manly bonding than you’d find in your average Ken Takakura or Koji Tsuruta film.

Sentimental drama is not avoided though: the film features Nikkatsu’s regular wallflower Chieko Matsubara as a young woman with a missing brother and a sick kid to take care of.

Hideki Takahashi is the main character in Biographies of Killers, a yakuza joining a gang of killers to make some money. He later runs into Matsubara, who doesn’t know he’s a yakuza and indirectly related to his missing brother who has been killed. There’s also a common yakuza film theme with poor workers being targeted by the yakuza. The storyline isn’t especially interesting and the lack of a strong plot hurts, but Nishimura’s direction is pretty good, often vitalizing quiet scenes with emotional tension.

Nishimura had a far more interesting screenplay to work with in Yakuza Native Ground (Yakuza bangaichi / やくざ番外地) (1969), which is a very good modern day set transitional era (ninkyo/jitsuroku) yakuza film. Tetsuro Tamba stars as a businessman-like gangster who builds his gang of youngsters willing to do the dirty work for him, including a psychotic hothead Jiro Okazaki. Tamba is pals with Kei Sato, a slightly more righteous boss in a rival gang, likewise leaving the quarrels to the youngsters while trying remain friends with Tamba.

Nishimura had a far more interesting screenplay to work with in Yakuza Native Ground (Yakuza bangaichi / やくざ番外地) (1969), which is a very good modern day set transitional era (ninkyo/jitsuroku) yakuza film. Tetsuro Tamba stars as a businessman-like gangster who builds his gang of youngsters willing to do the dirty work for him, including a psychotic hothead Jiro Okazaki. Tamba is pals with Kei Sato, a slightly more righteous boss in a rival gang, likewise leaving the quarrels to the youngsters while trying remain friends with Tamba.

Yakuza Native Ground takes a while to get going with some seemingly random side plots, which however all come together big time when Tamba’s sister falls in love with a young man associated with the rival gang, and then all hell starts breaking loose, leading to a well orchestrated final massacre. There’s also an interesting mix of ninkyo-like honour themes and jitsuroku shades of gray, especially evident in Tamba’s well written character. Nishimura’s character direction is effective and it’s always a pleasure to see Tamba in starring roles.

Films like Yakuza Native Ground and Kaettekita ookami make one wonder what other cool films are still waiting to be discovered in Nishimura’s 1960s filmography. There’s hoping that one day all of them will be available for viewing. It might be a bit of a stretch to declare Nishimura a as forgotten master, but he was certainly an interesting filmmaker capable of delivering enjoyable, even exhilarating pictures when given a good screenplay.

This was probably Toei’s first delinquent girl film. Five minutes into it we’re already treated a massive street brawn between two delinquent girl gangs. Charming chap Ken Takakura is a young intellectual of a modern business oriented yakuza group whose game centre the female delinquents populate. Takakura comes up with a plan: take the gals on a hot springs trip and educate them in arts – could rehabilitate them and turn into a profit in the long run.

This was probably Toei’s first delinquent girl film. Five minutes into it we’re already treated a massive street brawn between two delinquent girl gangs. Charming chap Ken Takakura is a young intellectual of a modern business oriented yakuza group whose game centre the female delinquents populate. Takakura comes up with a plan: take the gals on a hot springs trip and educate them in arts – could rehabilitate them and turn into a profit in the long run.

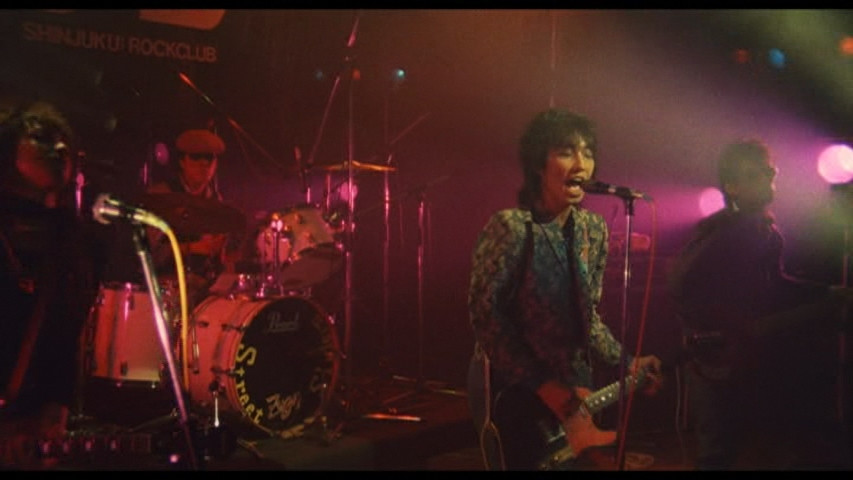

Incoherent, yet fascinating youth docu-drama from Japan’s golden era of educational problems (*). The film opens with live recording of The Street Sliders performing their rock hit “Masturbation” (?!) and then proceeds cut back and forth between two separate storylines for the rest of the movie. The first one features a band-affiliated girl (Kazumi Kawai) exploring the ambivalent Tokyo in a strictly specified 24 hour timeframe in mid November. The other follows a transfer student (real life delinquent Namie Takada) being a bully bitch in different, loosely specified timeframe spanning about one year and partially overlapping with the 1st story.

Incoherent, yet fascinating youth docu-drama from Japan’s golden era of educational problems (*). The film opens with live recording of The Street Sliders performing their rock hit “Masturbation” (?!) and then proceeds cut back and forth between two separate storylines for the rest of the movie. The first one features a band-affiliated girl (Kazumi Kawai) exploring the ambivalent Tokyo in a strictly specified 24 hour timeframe in mid November. The other follows a transfer student (real life delinquent Namie Takada) being a bully bitch in different, loosely specified timeframe spanning about one year and partially overlapping with the 1st story. The post WWII Japan had experienced a period of respect towards educators as people saw education as a way out of poverty, but with the economic miracle and improved living conditions it seems some students seized to see teachers as invaluable. At the same time high school entrance rates were gradually going towards the roof (today it’s nearly 100%) as entrance became something that was expected of everyone. Soon every dumbass regardless of academic skill and suitability was going to high school. Unsurprisingly, problems would escalate especially in lower level private schools that accepted essentially any student whose parents were willing to pay tuition. There were students who were yankis or bosozoku biker gang members, and violence, bullying and even suicides ensued.

The post WWII Japan had experienced a period of respect towards educators as people saw education as a way out of poverty, but with the economic miracle and improved living conditions it seems some students seized to see teachers as invaluable. At the same time high school entrance rates were gradually going towards the roof (today it’s nearly 100%) as entrance became something that was expected of everyone. Soon every dumbass regardless of academic skill and suitability was going to high school. Unsurprisingly, problems would escalate especially in lower level private schools that accepted essentially any student whose parents were willing to pay tuition. There were students who were yankis or bosozoku biker gang members, and violence, bullying and even suicides ensued.

The leaps of development in loosening censorship, and pushing the envelope in terms of what was acceptable in a major studio film, were huge in the late 60s and early 70s Japan. The first Hot Springs Geisha (1968) film, a harmless resort sex comedy and one of Teruo Ishii’s dullest efforts, only managed to sneak in one or two brief topless shots. This sequel, which hit the screens 12 months later, by first time director Misao Arai, manages more in its opening credits scene alone, which consists entirely of a peeping Tom zooming into bathing girls’ breasts for the viewer’s pleasure.

The leaps of development in loosening censorship, and pushing the envelope in terms of what was acceptable in a major studio film, were huge in the late 60s and early 70s Japan. The first Hot Springs Geisha (1968) film, a harmless resort sex comedy and one of Teruo Ishii’s dullest efforts, only managed to sneak in one or two brief topless shots. This sequel, which hit the screens 12 months later, by first time director Misao Arai, manages more in its opening credits scene alone, which consists entirely of a peeping Tom zooming into bathing girls’ breasts for the viewer’s pleasure. Not exactly a great film overall, and it does have its boring bits here and there, but plenty more fun that you might expect. This is as good if not better than the two Norifumi Suzuki directed instalments (parts 4 and 5) which followed with a bit of delay.

Not exactly a great film overall, and it does have its boring bits here and there, but plenty more fun that you might expect. This is as good if not better than the two Norifumi Suzuki directed instalments (parts 4 and 5) which followed with a bit of delay. Director Shogoro Nishimura was best known for his Roman Porno films, which have always enjoyed immense commercial popularity despite their modest cinematic merits. However, before Nishimura became a Roman Porno vending machine, he was a yakuza and youth film director at Nikkatsu. Those early films, which account to 14 in total, made between 1963 and 1970, reveal a far more interesting filmmaker than the gun-for-hire that most people know him as.

Director Shogoro Nishimura was best known for his Roman Porno films, which have always enjoyed immense commercial popularity despite their modest cinematic merits. However, before Nishimura became a Roman Porno vending machine, he was a yakuza and youth film director at Nikkatsu. Those early films, which account to 14 in total, made between 1963 and 1970, reveal a far more interesting filmmaker than the gun-for-hire that most people know him as. Nishimura’s directorial debut was the 1963 film The Gambling Monk (Keirin shônin gyôjyôki / 競輪上人行状記), based on a screenplay by Shohei Imamura and Nobuyuki Onishi. The film is a biting black comedy/drama about a mischievous middle school teacher (Shoichi Ozawa) who becomes a gambling addicted monk following his brother’s death. He tries to take care of his family temple business, but gets mixed up in bicycle betting, alcohol and desperate women.

Nishimura’s directorial debut was the 1963 film The Gambling Monk (Keirin shônin gyôjyôki / 競輪上人行状記), based on a screenplay by Shohei Imamura and Nobuyuki Onishi. The film is a biting black comedy/drama about a mischievous middle school teacher (Shoichi Ozawa) who becomes a gambling addicted monk following his brother’s death. He tries to take care of his family temple business, but gets mixed up in bicycle betting, alcohol and desperate women. Nishimura got his second chance at directing in 1966 with the excellent Sun Tribe film Kaettekita ookami (帰ってきた狼). The story kicks off when a mixed blood, misunderstood loner (Ken Yamauchi) drifts back into a small seaside town where he slew a man years ago. Around the same time a super hot yacht girl Rika, who is a bit of a spoiled brat, sails to the shores. She has instant hot for him, and her bloated self ego takes a hit when he says he just digs her yacht. Then there is the film’s actual protagonist (Junichi Kagiyama), a cowardish but decent guy and the only rational one of the bunch, as well as some local teen hoods giving everyone trouble.

Nishimura got his second chance at directing in 1966 with the excellent Sun Tribe film Kaettekita ookami (帰ってきた狼). The story kicks off when a mixed blood, misunderstood loner (Ken Yamauchi) drifts back into a small seaside town where he slew a man years ago. Around the same time a super hot yacht girl Rika, who is a bit of a spoiled brat, sails to the shores. She has instant hot for him, and her bloated self ego takes a hit when he says he just digs her yacht. Then there is the film’s actual protagonist (Junichi Kagiyama), a cowardish but decent guy and the only rational one of the bunch, as well as some local teen hoods giving everyone trouble. Following Kaettekita ookami, Nishimura helmed a number of other films I have not had the pleasure of seeing. However, his 1967 effort Burning Nature (Hana wo kuu mushi / 花を喰う蟲) offers further evidence that Nishimura is indeed remembered for the wrong films. This one starts out as a breezy youth film but soon morphs into a study of greed and moral corruption as a wildcat girl (Taichi Kiwako) runs into a manipulative “businessman” (Hideaki Nitani) who promises her a career as a model. She finds success due to her good looks, but also learns that that is exactly her worth the in the modern world.

Following Kaettekita ookami, Nishimura helmed a number of other films I have not had the pleasure of seeing. However, his 1967 effort Burning Nature (Hana wo kuu mushi / 花を喰う蟲) offers further evidence that Nishimura is indeed remembered for the wrong films. This one starts out as a breezy youth film but soon morphs into a study of greed and moral corruption as a wildcat girl (Taichi Kiwako) runs into a manipulative “businessman” (Hideaki Nitani) who promises her a career as a model. She finds success due to her good looks, but also learns that that is exactly her worth the in the modern world. Not all early Nishimura films were great, though. Tokyo Streetfighting (Tokyo Shigai sen / 東京市街戦) (1967) is a case in point. Tetsuya Watari’s theme song is the only good thing about this half-arsed Nikkatsu yakuza action film. It’s yet another tale of people coping in the ruins of Tokyo in the post WW2 Japan, with a couple of good men (Watari, Joe Shishido) standing against the exploitative Korean gangsters. Toei also made several films like this, some of them good (True Account of Ginza Tortures, 1973), some as bad as this (Third Generation Boss, 1974; Kobe International Gang, 1975).

Not all early Nishimura films were great, though. Tokyo Streetfighting (Tokyo Shigai sen / 東京市街戦) (1967) is a case in point. Tetsuya Watari’s theme song is the only good thing about this half-arsed Nikkatsu yakuza action film. It’s yet another tale of people coping in the ruins of Tokyo in the post WW2 Japan, with a couple of good men (Watari, Joe Shishido) standing against the exploitative Korean gangsters. Toei also made several films like this, some of them good (True Account of Ginza Tortures, 1973), some as bad as this (Third Generation Boss, 1974; Kobe International Gang, 1975). Another example of lesser efforts in Nishimura’s filmography is Biographies of Killers (Shikakû rêtsuden / 刺客列伝) (1967). Nikkatsu was in general best known for their contemporary films, however, they also produced scores of period yakuza films. I am far from well educated in Nikkatsu’s yakuza output, but compared to Toei’s ninkyo films, this movie at least is somewhat grittier in philosophy (as suggested by the title), leaving less room for chivalry, stoic pathos and manly bonding than you’d find in your average Ken Takakura or Koji Tsuruta film.

Another example of lesser efforts in Nishimura’s filmography is Biographies of Killers (Shikakû rêtsuden / 刺客列伝) (1967). Nikkatsu was in general best known for their contemporary films, however, they also produced scores of period yakuza films. I am far from well educated in Nikkatsu’s yakuza output, but compared to Toei’s ninkyo films, this movie at least is somewhat grittier in philosophy (as suggested by the title), leaving less room for chivalry, stoic pathos and manly bonding than you’d find in your average Ken Takakura or Koji Tsuruta film.  Nishimura had a far more interesting screenplay to work with in Yakuza Native Ground (Yakuza bangaichi / やくざ番外地) (1969), which is a very good modern day set transitional era (ninkyo/jitsuroku) yakuza film. Tetsuro Tamba stars as a businessman-like gangster who builds his gang of youngsters willing to do the dirty work for him, including a psychotic hothead Jiro Okazaki. Tamba is pals with Kei Sato, a slightly more righteous boss in a rival gang, likewise leaving the quarrels to the youngsters while trying remain friends with Tamba.

Nishimura had a far more interesting screenplay to work with in Yakuza Native Ground (Yakuza bangaichi / やくざ番外地) (1969), which is a very good modern day set transitional era (ninkyo/jitsuroku) yakuza film. Tetsuro Tamba stars as a businessman-like gangster who builds his gang of youngsters willing to do the dirty work for him, including a psychotic hothead Jiro Okazaki. Tamba is pals with Kei Sato, a slightly more righteous boss in a rival gang, likewise leaving the quarrels to the youngsters while trying remain friends with Tamba.

Exciting delinquent girl drama is in equal parts a youth film and a blazing gangster movie set to “live” music à la Walter Hill’s Streets of Fire. First timer Yuko Watanabe stars as an Osaka bad girl who’s introduced to the world of indie rock bands by a friendly biker gay hanging out in a small a rock bar. The film was cast with open auditions, most of the sukeban girls being obvious real delinquents with wonderfully coarse Osaka dialects. The film is also packed with 80s heavy metal bands and rock stars with mindblowing names (Mad Rocker, Jesus, Christ etc.)

Exciting delinquent girl drama is in equal parts a youth film and a blazing gangster movie set to “live” music à la Walter Hill’s Streets of Fire. First timer Yuko Watanabe stars as an Osaka bad girl who’s introduced to the world of indie rock bands by a friendly biker gay hanging out in a small a rock bar. The film was cast with open auditions, most of the sukeban girls being obvious real delinquents with wonderfully coarse Osaka dialects. The film is also packed with 80s heavy metal bands and rock stars with mindblowing names (Mad Rocker, Jesus, Christ etc.)