Maniac Driver (マニアック・ドライバー) (Japan, 2021)

This is a bit of a hastily put together review, but here goes: It’s good for a film to show its true colors in the very beginning. Maniac Driver opens with a leather-gloved, motorbike-helmet wearing killer stalking a naked woman who is touching herself in the shower. “A Japanese Giallo” appears on screen before the killer pulls out his knife out and rams it through hear breast, after first slicing her nipple in half. All is set to an unmistakably retro 80s score and against a psychedelic colour design.

It’s good for a film to show its true colors in the very beginning. Maniac Driver opens with a leather-gloved, motorbike-helmet wearing killer stalking a naked woman who is touching herself in the shower. “A Japanese Giallo” appears on screen before the killer pulls out his knife out and rams it through hear breast, after first slicing her nipple in half. All is set to an unmistakably retro 80s score and against a psychedelic colour design.

It’s a little questionable if a film that features little mystery, and reveals the killer’s identity in its opening scene, matches the expectations of a “pure” giallo. But that’s debatable. What’s more important to note is that Maniac Driver isn’t going to challenge Deep Red, or really even Tenebre, but rather Strip Nude for Your Killer. Director Kurando Mitsutake has clearly set his aim at the sleaziest genre film imaginable, and in that regard, oh boy, does he deliver.

The film’s title driver is a mentally disturbed Tokyo cabbie searching for a sacrificial victim to die with. Flashbacks reveal his wife fell under the knife of a masked killer. Now the driver has gotten himself an identical outfit and a blade, and is seeking to perform an ecstatic knife murder that would provide him with a release and let him also take his own life.

Mitsutake is best known for his genre-celebrations. The samurai spaghetti tribute Samurai Avenger: The Blind Wolf (2009) crumbled under the weight of its near-endless genre references, but the subsequent Gun Woman (2014) and Karate Kill (2016) found a voice of their own while paying loving tribute to other films. Now Mitsutake goes heavy on borrowing from his influences again. The New York Ripper and other gialli are present here, as are Maniac (1980) and its remake (2012). Evil Dead Trap (1988) comes to mind in one scene, and the helmet is probably sourced from Nightmare Beach (1989). There’s even a brief samurai swordfight, that soon turns into Nikkatsu style SM-sleaze featuring a “noble lady” (actually hostess, but the costume and attitude are about the same) not too different from Flower and Snake. (1974) or Wife to be Sacrificed (1974).

Pink films are the film’s 2nd important reference. There are two long sex scenes (complete with slow-motion bouncing boobs) and two shorter solo-sex scenes, in addition to which all women (every single one, minus the extras) lose their robe, particularly at the time of their death. Some might feel inclined to call the director a misogynist! But this isn’t a film for them anyway. And the skin springs from deeper down the film’s production roots. Mitsutake says he was originally offered a pink film to direct, with supposedly unlimited artistic freedom. However, the financing fell apart on the last moment when the company fully realized what Mitsutake was about to shoot for them and started imposing restrictions. Mitsutake walked out and shot the script as it was without the studio, with producer Mami Akari pulling the necessary funds out of her own pocket. The cast remained unchanged, explaining why every actress in the film is an AV performer (and not quite A-listers either). The resulting film is, uhm, a maniac mixture of sleazy sexsploitation and low-budget knifing. The filmmakers identify Maniac Driver as a giallo, and in that regard the film sets itself against some cinematic masterpieces whose production values it couldn’t dream of approaching. For instance, the lighting in the murder scenes is pure 70s Argento, but with the limited production values it comes out more like Hobo with a Shotgun. That’s not saying the scenes aren’t fun to watch, however, as Mitsutake rocks at mixing music with images. What we have here appears even more impressive once you learn Mitsutake had to shoot the film in just 4½ days (the last shooting session was 50 hours non-stop, he says)!

The resulting film is, uhm, a maniac mixture of sleazy sexsploitation and low-budget knifing. The filmmakers identify Maniac Driver as a giallo, and in that regard the film sets itself against some cinematic masterpieces whose production values it couldn’t dream of approaching. For instance, the lighting in the murder scenes is pure 70s Argento, but with the limited production values it comes out more like Hobo with a Shotgun. That’s not saying the scenes aren’t fun to watch, however, as Mitsutake rocks at mixing music with images. What we have here appears even more impressive once you learn Mitsutake had to shoot the film in just 4½ days (the last shooting session was 50 hours non-stop, he says)!

Another weakness is that the film doesn’t invest as much in suspense as it does in totally overdone exploitation. Maniac Driver is actually at its best in some of its quieter moments, such as when the melancholic cabbie is cruising in the Tokyo night (with some great time-lapse footage) or practicing his knife combos in from of a mirror gleaning in red and blue. Only Mitsutake he had exercised similar restraint in the murder scenes and refrained from having the driver appear butt naked behind a victim’s door and then chase her while rock music plays and his balls are hanging out (though an admirable scene on its own, sort of!), the suspense might have been on a whole different level.

Thematically one of the film’s most interesting aspects is – the way I perceived it at least – is just how much the main characters comes out as homicidal incel. I wonder if it was a pure coincidence that the maniac, whose narrator voice babbles about the mad society, men and women, and his desire to kill people before he takes his own life, commits his first murder in mid-October 2019. That about a week after incel landmark film Joker opened in Japanese theaters. Perhaps a coincidence.

Maniac Driver is a bit of a tough one to evaluate. It takes its exploitation to the point of being ridiculous, feasts in low-budget aesthetics, and really dives deep in the pink end of the pool. There are bits that I think miss the mark, such as the convoluted climax and closing the film on a pink note. Gialli have been done better before, including the Japanese one (Zoom In: Sex Apartments, 1980). Yet, it’s impossible not to enjoy such a frank, no-holds-barred exploitation filmmaking that we have here. There are scenes where Mitsutake paints the screen red from the bottom of his heart, does it without resorting to CGI splatter, and even manages to pull odd fascination from the film’s messy doom’s day mixture of genres and influences. And there’s no denying the beauty of the film’s more atmospheric moments, a testament to just how good Mitsutake can be. You won’t be bored for a moment! I wasn’t, and I’ve seen it twice.

Reviewed at Yubari Fanta 2021 Online Edition

A standard ninkyo film with honourable yakuza Koji Tsurura going against merciless, but not entirely rotten businessman gangster Tetsuro Tamba. There are too many talking heads scenes and a storyline that isn’t awfully interesting, but also solid filmmaking and drama that sneaks into the film almost unnoticed. Tamba is always interesting, and the bloody final sword duel against him is quite powerful. There’s also some old fashioned charm stemming from an extensive use of songs, which shouldn’t necessarily be surprising since Toei’s prominent enka singer actors Hideo Murata and Saburo Kitajima are both in the film.

A standard ninkyo film with honourable yakuza Koji Tsurura going against merciless, but not entirely rotten businessman gangster Tetsuro Tamba. There are too many talking heads scenes and a storyline that isn’t awfully interesting, but also solid filmmaking and drama that sneaks into the film almost unnoticed. Tamba is always interesting, and the bloody final sword duel against him is quite powerful. There’s also some old fashioned charm stemming from an extensive use of songs, which shouldn’t necessarily be surprising since Toei’s prominent enka singer actors Hideo Murata and Saburo Kitajima are both in the film. An absolutely astonishing art house ninkyo yakuza film by Masashige Narusawa. Wandering gambler Tatsuo Umemiya runs into a young swindler woman Haruko Wanibuchi working with old man Junzaburo Ban. They are both arrested by detective Ko Nishimura. A year later Umemiya is staying with gangster Tatsuo Endo when he comes across that woman and her partner again. Endo lusts for both her and his own daughter, while Endo’s looney yakuza brother Toru Abe has a thing for Endo’s daughter, who in turn has her eye on Umemiya, and is willing to annihilate people standing on her way. And here lies one of the film’s remarkable departures from the standard ninkyo efforts: it doesn’t have a third party villain, nor a clear distinction between good and evil. It’s bursting with romantic emotion and wrenched with gritty realism, shot with striking black and white compositions, and explodes into shocking carnage. It has lengthier, more detailed gambling scenes than any other yakuza film I’ve seen. And it has a heartbreakingly beautiful score. You could call it the Ashes of Time of ninkyo yakuza films. A masterpiece!

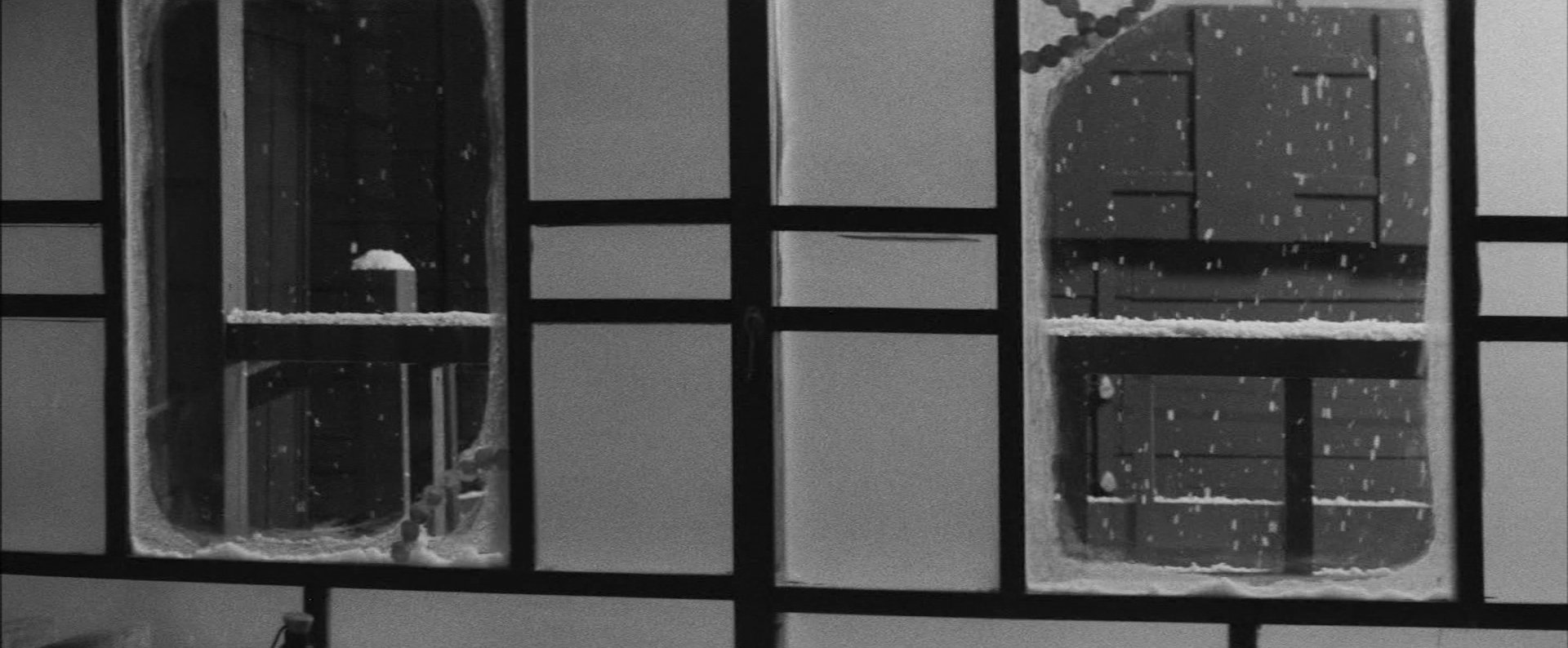

An absolutely astonishing art house ninkyo yakuza film by Masashige Narusawa. Wandering gambler Tatsuo Umemiya runs into a young swindler woman Haruko Wanibuchi working with old man Junzaburo Ban. They are both arrested by detective Ko Nishimura. A year later Umemiya is staying with gangster Tatsuo Endo when he comes across that woman and her partner again. Endo lusts for both her and his own daughter, while Endo’s looney yakuza brother Toru Abe has a thing for Endo’s daughter, who in turn has her eye on Umemiya, and is willing to annihilate people standing on her way. And here lies one of the film’s remarkable departures from the standard ninkyo efforts: it doesn’t have a third party villain, nor a clear distinction between good and evil. It’s bursting with romantic emotion and wrenched with gritty realism, shot with striking black and white compositions, and explodes into shocking carnage. It has lengthier, more detailed gambling scenes than any other yakuza film I’ve seen. And it has a heartbreakingly beautiful score. You could call it the Ashes of Time of ninkyo yakuza films. A masterpiece!

This was probably Toei’s first delinquent girl film. Five minutes into it we’re already treated a massive street brawn between two delinquent girl gangs. Charming chap Ken Takakura is a young intellectual of a modern business oriented yakuza group whose game centre the female delinquents populate. Takakura comes up with a plan: take the gals on a hot springs trip and educate them in arts – could rehabilitate them and turn into a profit in the long run.

This was probably Toei’s first delinquent girl film. Five minutes into it we’re already treated a massive street brawn between two delinquent girl gangs. Charming chap Ken Takakura is a young intellectual of a modern business oriented yakuza group whose game centre the female delinquents populate. Takakura comes up with a plan: take the gals on a hot springs trip and educate them in arts – could rehabilitate them and turn into a profit in the long run.

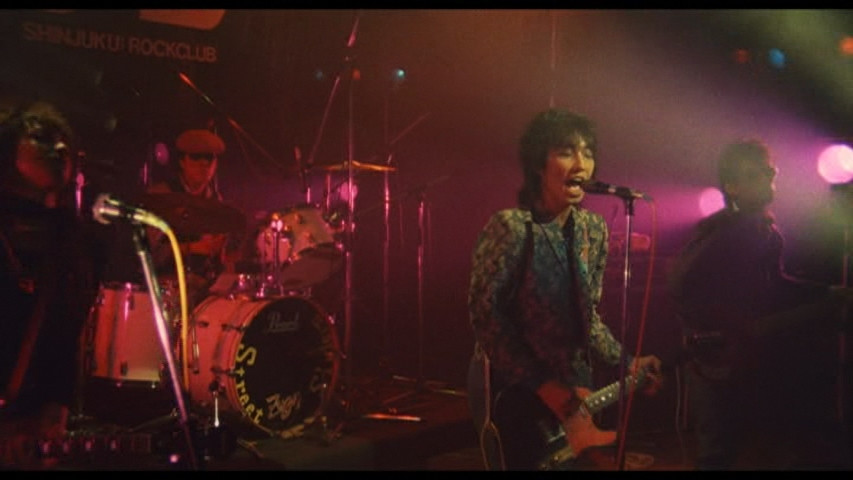

Incoherent, yet fascinating youth docu-drama from Japan’s golden era of educational problems (*). The film opens with live recording of The Street Sliders performing their rock hit “Masturbation” (?!) and then proceeds cut back and forth between two separate storylines for the rest of the movie. The first one features a band-affiliated girl (Kazumi Kawai) exploring the ambivalent Tokyo in a strictly specified 24 hour timeframe in mid November. The other follows a transfer student (real life delinquent Namie Takada) being a bully bitch in different, loosely specified timeframe spanning about one year and partially overlapping with the 1st story.

Incoherent, yet fascinating youth docu-drama from Japan’s golden era of educational problems (*). The film opens with live recording of The Street Sliders performing their rock hit “Masturbation” (?!) and then proceeds cut back and forth between two separate storylines for the rest of the movie. The first one features a band-affiliated girl (Kazumi Kawai) exploring the ambivalent Tokyo in a strictly specified 24 hour timeframe in mid November. The other follows a transfer student (real life delinquent Namie Takada) being a bully bitch in different, loosely specified timeframe spanning about one year and partially overlapping with the 1st story. The post WWII Japan had experienced a period of respect towards educators as people saw education as a way out of poverty, but with the economic miracle and improved living conditions it seems some students seized to see teachers as invaluable. At the same time high school entrance rates were gradually going towards the roof (today it’s nearly 100%) as entrance became something that was expected of everyone. Soon every dumbass regardless of academic skill and suitability was going to high school. Unsurprisingly, problems would escalate especially in lower level private schools that accepted essentially any student whose parents were willing to pay tuition. There were students who were yankis or bosozoku biker gang members, and violence, bullying and even suicides ensued.

The post WWII Japan had experienced a period of respect towards educators as people saw education as a way out of poverty, but with the economic miracle and improved living conditions it seems some students seized to see teachers as invaluable. At the same time high school entrance rates were gradually going towards the roof (today it’s nearly 100%) as entrance became something that was expected of everyone. Soon every dumbass regardless of academic skill and suitability was going to high school. Unsurprisingly, problems would escalate especially in lower level private schools that accepted essentially any student whose parents were willing to pay tuition. There were students who were yankis or bosozoku biker gang members, and violence, bullying and even suicides ensued.